ahwazian-Iranian Demographic Conflict, Mechanisms and Cause

ahwazian-Iranian Demographic Conflict, Mechanisms and Cause

Non-military, systemic conflict is one of the most effective and influential types of modern global conflict. One of the most prominent varieties of such a conflict is demographic conflict, meaning an effort by the aggressor to change the population structure and alter the original demographic makeup of a region in the aggressor’s favour. This is what we see in Ahwaz at the hands of successive Iranian regimes with the aim of eliminating the indigenous Ahwazi people’s identity and replacing it with a Persian population. Since 1950 to the present day, more than 2,000,000 Persians have been resettled and employed in Ahwaz to take up jobs in the petrochemical sector and government departments, both of which are denied to the local Ahwazi people, with housing especially provided for these non-Ahwazi migrants. Meanwhile, Ahwazis, denied jobs and often driven from their homes, are forced to migrate to Persian cities such as Isfahan, Shiraz, Yazd, Tehran and other cities in search of usually low-paid, unskilled jobs provided by the Islamic Republic and its predecessors for this goal and this purpose. In 2017, the AsrIran website quoted the current governor Gholamreza Shariati as stating that between 2011 and 2016 more than 200,000 Ahwazis migrated to Persian cities in search of work and employment (Shariati, 2017).

This study provides an Ahwazi perspective and analysis of this demographic conflict, and the Ahwazi people’s resistance towards this policy which is effectively one of Iranian domestic colonisation, addressing the reasoning of both parties in the conflict and detailing the measures adopted in resistance and defiance by the Ahwazi people engaged in an unjust and imbalanced conflict such as this one which has lasted for more than nine decades to date, ever since the 1925 occupation of Ahwaz and the capture of its Emir up until the current day.

This study examines the causes of the Ahwazi-Iranian demographic conflict according to the socio-economic and political phenomena experienced by Ahwazis in the current conditions. We will also analyse the strategies and plans used by the Iranian regime in its efforts to change Ahwazi demography in order to homogenise and ‘Persianise’ Ahwaz by dispersing the indigenous Ahwazi people or merging them with the migrant Persians in the Ahwazi areas, eradicating Ahwazi identity.

The study is important from an official perspective as it relies on official and purportedly accurate statistics taken from state-run Iranian agencies and ministries which produce these figures and use them as their primary statistical source material.

First: Concept of Conflict, Demography and the Demographic Conflict (Geopolitical):

Conflict:

The concept of conflict in specialist political literature is viewed as a dynamic phenomenon. It is worth noting that the phenomenon of international conflict is unique to international relations as an extremely complex dynamic phenomenon. This is due to its multiple dimensions, the overlap between its causes and sources and their direct and indirect interactions and effects, and the varying levels at which it occurs in terms of the extent or intensity of violence – or other, non-direct forms of aggression seen in non-violent conflict. This means that such a conflict at its core expresses a conflict between national administrations, resulting from differences in motives, perceptions, objectives, aspirations, resources, capabilities, etc., which in the final analysis lead to making decisions or pursuing policies that differ more than they agree. However, such a conflict, despite all its tensions and pressures, does not reach the point of armed war, retaining a space for conflict management or adaptation to its pressures while maintaining the relative ability to choose between the alternatives available for each party.

Demography:

Demography, known as population science, refers to the study of a range of population characteristics. These are quantitative characteristics, including population density, distribution, growth, size and population structure; as well as qualitative characteristics, including those related to nationality, identity, and religion. It also includes social elements such as: development, education, nutrition and wealth. Demography is defined as statistics that include income, births, deaths, etc., which contribute to the clarification of human changes. Among the other definitions is that of a statistical, social and vital science based on studying a set of statistics related to individuals (Kheder, 2018).

Demographic Conflict or Demographic (Geopolitical) Wars:

Demographic change and cleansing in a comprehensive manner is based on the practice of the policy of transfer (quiet expulsion) in all its varieties in terms of geography and population composition, such as reducing the overall fertility rate of women through encouraging higher than usual caesarean birth rates, and the policy of instigating an environment in which psychological diseases and crises flourish, as well as failing to reduce the prevalence of chronic and deadly diseases such as kidney diseases, cancer, skin diseases and respiratory problems. Also, the geopolitical dimension is used to change the physical geography of the location and gradually destroy those resources essential to the survival and wellbeing of the indigenous population through using all available strategies, denying them every possible means of securing a livelihood and disregarding their fundamental right as indigenous inhabitants whose ancestors have owned the lands in question for generations in order to replace them with migrant incomers who will who support the policies of the usurping regimes.

Demographic conflict is a form of indirect war, complete with non-military attacks from the authority and resistance from the axes of popular resistance. Those states and regimes using this strategy are always keen to enforce their projects to change the local demography, making occasional small concessions to axes of resistance and even offering limited capabilities to some as a means of pacification, while always taking a long-term perspective to ensure an outcome in their own interest in future years and decades. By contrast, there is no similar plan or structure to the opposition of the indigenous popular resistance’s political or social groupings in their conflict with regimes engaged in these wars, with their opposition being of an impromptu defensive nature responding to the aggressor’s predations and apparent attempts to obliterate and marginalise them. In the absence of any objective local authority in such cases, it is difficult and often virtually impossible for those engaged in resistance to formulate and implement a strategy since their future vision is reactive, spontaneous and organic, arising largely from the groups on the ground in the areas affected. Meanwhile, the aggressors’ policy of attrition of capacities and their suppression of popular movements limits the ability of the resistance to formulate a unified view on how best to confront the well-planned strategies by the aggressors engaged in this relentless demographic warfare (Ahmed, 2012).

The need to enforce such demographic changes in the territory in question and the resulting demographic conflict are vital considerations for the ruling regimes and powers, particularly when an expansionist imperial power is confronting a group differing in ethnicity, culture or religion and resistant to its ideology. Syria is an important case in point in this context, with Iranian regime officials quoted as saying that if Syria was lost to the regime, it would not be able to hold onto Tehran! The same applies in both historic and contemporary settings, with the genocidal Roman occupation of Judea, the brutal Iranian occupation of the provinces of Kurdistan and Baluchistan, the refusal of the People’s Republic of China to accept the independence of Taiwan, the harsh and oppressive Communist Chinese occupation of Tibet, and the oppressive persecution by the Communist Chinese government of the Muslim Uighurs in Sinjiang province.

Second: Demographic conflict in Ahwaz:

A. Demographic change in Ahwaz and its effects

B: Iranian role in demographic change and demographic conflict

C: Population change and its effects

D: Geographical change and its effects

E: Medical and health demographic change

When terms such as “demographic conflict” or “geopolitical demographic war” appear, this shows that we are looking at the age-old phenomenon of the perpetual conflict between the coloniser and the colonised.

The Ahwazi-Iranian demographic conflict is characterised by special circumstances which mean that it poses a major threat to the Ahwazi people in terms of resistance, and that it is very different from other colonial conflicts; in the Ahwazi case, the conflict is characterised as a non-religious conflict, accompanied by a struggle over gradual displacement in contrast to other demographic conflicts in which there is a far more evident religious-nationalist element which is declared against the oppressed peoples through means of weapons and military force – in these cases, the thwarting of such a military offensive and the victory of either the occupying state or those whose lands it wishes to colonise is always relatively quick and decisive.

By contrast, in Ahwaz the Iranian occupying state wears the cloak of Shia Islam, the faith and sect shared by most of the colonised people, to impose its policies and controls the clergy who are spread throughout the Ahwazi society in Ahwaz, using these clerics as a legitimising apparatus to protect it and deter any revolt against it. In its public rhetoric, the Iranian government adopts the language of humanitarianism and loudly voices its aversion to nationalism to dissuade Ahwazis from any move to adopt an Ahwazi nationalist stance or resort to nationalist conflict. However, if we disregard this lovely rhetoric and analyse the Iranian regime’s actual structure, divisions, behaviour and worldview, we find strong and clear racism and obvious discrimination inflicted on all Ahwazis. Another aspect making the Iranian regime’s policies in this demographic conflict more complex and dangerous is the regime’s constant defence and protection of the security of the ethnically Persian internal migrants from other areas of Iran supported by the regime’s judicial authorities and security apparatus, who depict any and all efforts by the indigenous Ahwazi people to resist colonisation and ethnic cleansing, reject the legitimacy of the occupying regime’s judicial and security services and defend their own rights as “terrorism” (Field source).

One of the instruments and aspects of this identity-based demographic conflict and of the other gradual and subtle policies to undermine Ahwaz through which the Iranian regime imposes its demographic change policies against Ahwazis is seen in the phenomenon of the “clash of the elites”, which often occurs between the racist Persian elite and the nationalist Ahwazi elite who are being marginalised and excluded from any potential benefits from the resources on their own lands. This is due to the misconception popularised by Persians since the 1925 colonisation that – contrary to all historical records – Ahwazis are the immigrant interlopers in this land and should return from where they came and that this status somehow gives Persians the right to their openly racist supremacist treatment and contempt for Ahwazis, the owners of the land, heritage, identity and soil. Historically, this supremacist worldview was the foundation for the Nazi creed and dehumanisation toward other races, indicating that while the expressed policy, objectives, and idea of the Persian occupation and others are nominally based on the concept of resistance, their implementation in reality varies according to subjects, location and time. The only clear ideology is gradual or sudden ‘demographic change’, as expressed, as we said earlier, in the term “transfer” (Ahmed, 2012).

A: Demographic change in Ahwaz and its effects:

Demographic change is the largest and most important concern for Ahwazis, since it affects their daily lives and identity and their future potential negatively as it has in all the previous decades since the fall of Arabistan (historical name of Ahwaz) to Iranian forces in 1925 and the killing of Emir Khazaal bin Jabir al-Kaabi in the first era of successive Persian Shahs’ rule. Ever since then, consecutive Iranian regimes have instituted deep-rooted policies of demographic change in the Ahwaz region through various means including murder, displacement, execution and destruction. These policies led most in Ahwaz to enthusiastically support the 1979 revolution, hoping to finally have justice and freedom. Even after Khomeinists seized power, instituting the ‘Islamic Republic’ theocracy, many Ahwazis, who are mostly Shiite, were at least initially deceived by the clerics into believing that their rule would be just and fair-minded, based on their positive views of the Khomeinists’ claims. While this brief period of acceptance allowed the new theocratic regime to institute and intensify the previous regime’s racist policies towards Ahwazis and to achieve some demographic transfer of the Ahwazi population, the new rulers were unable to achieve the comprehensive change they sought (AL- Abbar, 2017).

One of the main reasons for the large-scale demographic change in the region and its effects are unemployment, which is itself primarily caused by state-endorsed racial discrimination (Ahwazis are denied any rights or employment in all but the most menial jobs). Another is the regime’s wholesale destruction and pollution of the natural environment via oil and gas drilling, forcing thousands of farmers and fishermen to abandon their ancestral lands with no compensation, along with the regime’s destruction of countless villages, whose populations have been displaced in their thousands, again with no compensation, to make room for oil and gas drilling zones and refineries, along with the construction of purpose-built settlements created specifically to house the ethnically Persian workers imported from other parts of Iran to work in these facilities; it should be noted that Ahwazis are banned from living in these settlements which are provided with all the modern amenities denied to the indigenous Ahwazi people. These and other problems deliberately created by the regime to make life intolerable for the Ahwazi people have in turn led to further connected problems for Ahwazis, whose lives are dominated and devastated by the regime’s relentlessly hostile policies, leaving them in a constant state of conflict, with no meaningful way to repel or respond to the regime’s acts of non-military warfare, and with no option for resistance except to cling to their land and identity and to remain, despite everything, without retreating.

This systematic demographic change has affected people at every level, obviously and painfully in economic terms, as the only job opportunities available in Ahwaz are with petrochemical companies, oil refineries, sugarcane, traditional agriculture or free trade in the free market zones, with jobs in all these fields, except for the most unskilled and menial ones, closed to or almost non-existent for the Ahwazis . We will review these here, relying on the Iranian regime’s own official statistics and comments from its ministers and high-ranking officials and politicians with authority over these issues.

Petrochemicals:

Ever since the establishment of these vast state-run petrochemical facilities in Ahwaz – whose profits, according to international reports, go directly to support terrorism and the destabilisation of the region – the Iranian regime has withheld jobs from the local Ahwazi people using various pretexts, including the excuse that they lack the necessary qualifications or specialist skills; those Ahwazis with the requisite qualifications and skills will be turned down automatically on the supposed basis of a lack of experience or no vacancies, even when these jobs are still being advertised in Persian media. Meanwhile, applicants from ethnic Persian backgrounds and all other Iranian ethnicities can get the jobs effortlessly even without the necessary qualifications, skills and experience; this means the number of people employed in the petrochemicals industry in Ahwaz in the last decade has reached 300,000, all migrants, according to the regional governor , Shariati, in 2017, who provided the figures in a report about rising unemployment levels in Ahwaz (Shariati, 2017).

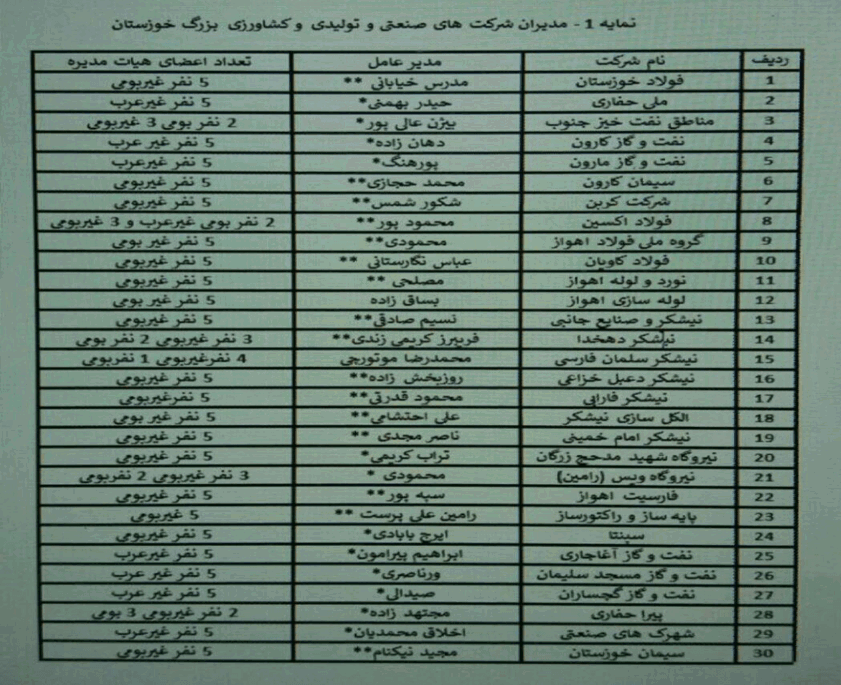

We also have detailed and accurate statistics on 30 of the petrochemical companies, oil and gas refineries, steel refineries and other companies in the region, which have no Ahwazis in any management or administrative roles.

Oil refineries:

A report published in the Feydus news agency in 2018 about employment in the Abadan oil refinery, the oldest and largest oil refinery in the Ahwaz region and one on which the regime in Tehran relies, Jalil Mokhtar, the representative of Abadan city in Iran’s parliament, said, more than 2,800 professionals, workers and technicians were employed in the refinery, only 1800 of whom were protected by the insurance service; of this number, only 340 local employees were identified as being from Abadan and Muhammarah .” ( Mokhtar, 2018).

Meanwhile, more than 80 per cent of the employees in the Bid Boland refinery in Arjan (Behbahan), are non-Ahwazi and migrants, according to a 2016 report by the Rahyab Agency (Rahyab, 2016).

Sugarcane farms:

The Iranian Revolutionary Guard Corps’ (IRGC) sugarcane farming project is one of the most environmentally devastating political projects launched in Ahwaz, with employees at these loss-making facilities being employed primarily on the basis of their affiliation with the IRGC and secondarily according to ethnicity and race, which aroused great anger and controversy in the Ahwaz street.

Traditional agriculture:

Agriculture provides the food for villages and outlying areas in Ahwaz, and the only means of livelihood for their indigenous inhabitants, who have lived there since time immemorial. The fertile lands and villages of Ahwaz are also, unfortunately for their peoples, located on top of subterranean oil, gas and mineral riches which are all that successive Iranian regimes care about, with the current regime being the worst to date. Many of the Ahwazi farmers, fishermen and owners of these lands have been marginalised and driven from their homes in order to turn the lands into vast oil and gas facilities, with the regime authorities adding insult to injury by placing dams near the source on the rivers to reroute most of their waters to ethnically Persian areas and even draining the marshlands they feed downstream, devastating the ecosystem and destroying what agriculture, farming and fishing remained, with the resulting drought afflicting the whole of Ahwaz, once renowned as a regional breadbasket. While the Iranian regime has offered some of the remaining farmers business opportunities, loans and jobs in the Persian cities in exchange for abandoning their lands, Ahwazis are fully aware that this is part of a malicious strategy to expel farmers so that new oil and gas facilities can be built on their lands.

The regime’s malice knows no bounds; for one example, when a heavier than usual seasonal rainfall in early 2019 ensured that the region’s farmers were expecting a bumper crop later that year, Iranian authorities deliberately opened the dams upstream to flood the lands downstream and destroy their crops in an attempt to force them to abandon their lands, offering services and facilities in other areas of Iran such as Isfahan, Tabriz and Yazd to encourage them to move, according to an official statement from Iran’s Ministry of Agriculture. Despite this effort, the persistently tenacious Ahwazis resisted the flooding with the most basic tools and refused to sell or abandon a single inch of their beloved lands for the sake of the regime in Tehran.

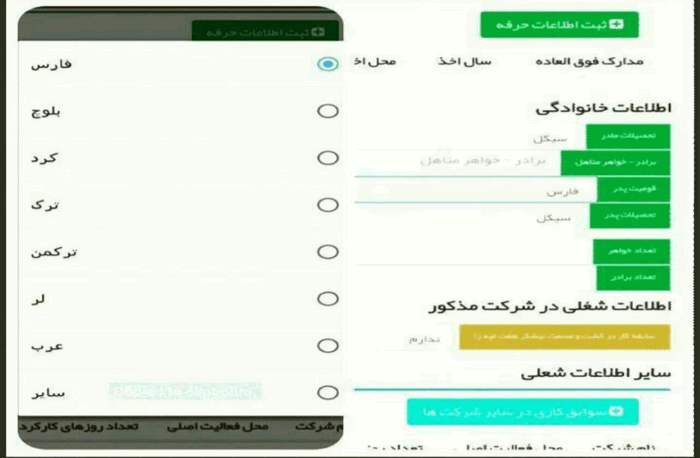

B: The Iranian role in demographic change and demographic conflict in Ahwaz is divided into two parts, namely the demographic change itself and the anti- Ahwazi racism of the Persians and the regime loyalists among the Lur, a nomadic people (demographic conflict). Whilst not wishing to openly admit its own racism, the regime supports and incites anti-Ahwazi racism amongst Persian and Lur personnel in ministries, schools and companies in the region in order to create an internal conflict and perpetual hostility among citizens in an effort to ensure division and to drain the people’s resistance capabilities and energies. The Lur, some of whom live in the north of Ahwaz, are nomadic migrants, mostly from Persian cities consider themselves to be historical existential and dangerous enemies of the Ahwazis; this clearly poses a threat to Ahwazi identity and sovereignty in their lands. This hostility, encouraged by Tehran has led to the Lurs claiming ownership of the land, providing the regime with another means of inciting further antagonism.

C: Population change and its effects:

The demographic change seen in Ahwaz has been carried out through the political mechanisms discussed above, with their effects being very apparent and obvious. Incoming settlers from other, ethnically Persian areas of Iran have taken over government jobs and positions, forcing the Ahwazi elite able to do so to migrate both within the borders of Iran and abroad. This demographic change is used to underline the regime’s claim that the Arabic language of the Ahwazi people is undesirable in government departments, schools and companies and to discourage residents from speaking or listening to it. For this reason, the Farsi language has become the official language used in the market, the street and all state bodies, despite this being contrary to Article 15 of the Iranian Constitution, which provides for the right to education in mother tongue for Ahwazis (Hamid, 2018).

Another effect is the commercial dimension in the market, with migrants taking over the local market and the trade sector within Ahwaz and boycotting local Ahwazi retailers and products sold by them. This has led to a further sharp upturn in migration amongst the Ahwazi elite, another of the effects of the regime’s unofficial but carefully calculated population transfer policy (Field source).

D. Geographical change and its impacts:

Geographical division is one of the most important methods of demographic change that limits the capabilities of any popular resistance movement. As such, this was the first method of demographic change deployed in Ahwaz under the Shah long before the 1979 revolution and continued ever since. Under the Shah, the Ahwaz region was divided between the provinces of Khuzestan, Bushehr and Bandar Abbas, with the former Arab names of the region’s cities and towns changed to Farsi, such as Muhammarah being renamed Khorramshahr, Abbadan renamed as Abadan, Falahiyeh renamed Shadegan, Ma’shour renamed as Mahshahr and Khafajiyeh renamed as Susangerd. Some outlying areas in the Ahwazi region were annexed to other provinces after the occupation of Ahwaz in 1925 to separate them and cut their strong ties with their Ahwazi community. This is in addition to the regime’s policy of attributing the ownership of the Ahwaz region to other, non- Ahwazi Iranian ethnicities and moving various ethnic Persians and other ethnicities to the region while forcing Ahwazis to migrate in an effort to make Ahwazis the smallest minority there.

Proof of demographic change:

A leaked copy of a 2014 report released by the Iranian regime’s ‘Supreme Council for National Security’ in 2016 provided further compelling evidence of the regime’s policy of ethnic cleansing of the Ahwazi population as part of the Iranian leadership’s ongoing efforts to permanently change the region’s demographic composition.

The leaked plan, named “A Comprehensive Security Project for Khuzestan”, proposed a number of strategies with the objective of crushing the Ahwazi freedom movement and thwarting already severely proscribed activism by the Ahwazis (alarabiya, 2016).

Perhaps the most important and dangerous of the items incorporated in this project is the planned construction of “new settlements and cities” to resettle massive numbers of Persian and other predominantly non-Arab immigrants from other areas of Iran in the region as a means of completely changing its demographic composition in favour of non-Ahwazi peoples to eradicate Ahwazi identity and culture.

According to the leaked report, the ‘security project’ was approved during a meeting of the higher council tasked by the SCNS with its implementation on 27 April 2014, with the meeting chaired by Abdolreza Rahmani Fazli, the Iranian Interior Minister under Hassan Rouhani’s government.

Ahwazi human rights organisations confirmed that the regime’s demographic change strategy is already being implemented, as noted above, via widespread land confiscation, seizure of properties, demolition of homes and population transfer, adding that whatever regime officials may claim, the evidence on the ground of these policies being brutally enforced is clear and unambiguous.

The measures proposed in the leaked report include “the repression of political movements” and “the continuation of the policy of demographic change by the displacement of Ahwazis from their home areas,” along with “bringing more Persians from other [Iranian] provinces for resettlement in the province of Khuzestan.”

In the report, a copy of which was received by Ahwazi rights groups, the author also – unusually for the regime – acknowledges “the existence of discrimination, oppression and marginalisation of Ahwazis in Khuzestan”, noting that this led to “nationwide protest” in recent years, before proposing further draconian security measures in an effort to prevent similar future protests. Unsurprisingly, none of the regime’s proposals include according the Ahwazi people the freedom and basic human rights for which activists and protesters are calling.

The report identifies five categories of challenges facing the Iranian regime in the Ahwaz region – “political, security, cultural, social and economic” – before proposing that these be resolved through focusing on quelling the demands of the Ahwazi peoples by “dissolving political mobility and demands in the crucible of Iranian pro-regime parties” through indoctrination of the region’s populace in the “concepts of the Islamic Republic” and inculcating “obedience to the Velayat e-faqih system”.

The higher council’s supervisory committee tasked with supervising the implementation of the project is staffed by senior regime officials including the First Assistant to the Iranian President, Eshaq Jahangiri Kouhshahi, as well as the Interior Minister, the Minister of Intelligence and his security and intelligence aides, and the commander of the regime’s regional Internal Security Forces. Another committee member is the chairman of the regime’s regional TV and radio media commission, while a number of members are not identified by name.

The SCNS was tasked by the regime leadership in 2014 with forming five sub-committees to implement the ‘security project’ over a five-year period up to 2019. The primary focus of the project, according to the leaked document, is the enactment of policies to eliminate regional threats and challenges to the regime, with the committees presenting biannual updates on their progress to SCNS Secretary-General Ali Shamkhani, who has overall charge of the project.

Prior to this leaked report, the Iranian regime’s plan to change the demographic composition of Ahwaz was first exposed in 2005 in another leaked document, which was signed by Mohammad Ali Abtahi, the policy director of former Iranian President Mohammad Khatami’s presidential office. Despite Abtahi’s denials of the document’s authenticity – a standard regime ploy – these revelations led to widespread protests across Ahwaz, dubbed the ‘April Ahwaz Uprising’, with hundreds of unarmed Ahwazi demonstrators killed by regime police and security forces in the leadership’s brutal crackdown (UNPO, 2017).

The unnamed author of the report also emphasised the crucial need for the regime to “reduce the migration of Persians from the Ahwaz region and ensure that they are settled there safely and securely, [and are] self-sufficient at all levels,” adding that there should be “increased emigration to the province of Khuzestan [North of Ahwaz] from other Iranian regions in order to ensure long-term demographic changes at the lowest cost.”

The report further recommended even more intense monitoring of human rights activism and diplomatic activity by Ahwazi activists both domestically and overseas, expressing concern that activists are attempting to raise awareness of their plight among the international community in order to gain international assistance and protection and to gain wider acknowledgement and recognition for the legitimacy of their cause.

The report author issued instructions for the immediate suppression of any calls for secession or federalism in Ahwaz, emphasising the need for the regime to limit the political activities of Ahwazis to those approved within the framework of the Islamic Republic and its institutions.

Another recommendation by the report’s author was the establishment of Arabic-language media channels which could disseminate negative propaganda about Ahwazi activism or “nationalism”, as well as countering “extremist groups” and “Wahhabism” in the region, with the regime also concerned at the number of young Ahwazis converting from Shi’ism to Sunnism despite facing severe penalties for doing so.

The report further recommended bringing Iraqi Shiite militias, as well as members of Lebanon’s Hezbollah, both of whom are currently fighting in Syria, to the region to help in the implementation of the ‘security project’. It suggested that this could be achieved by the Tehran-backed foreign militias holding seminars and giving talks to young Ahwazis to persuade them of the superiority of the Shi’ite doctrines as a means of dissuading them from supporting Ahwazi national movements domestically and overseas.

On the financing of the project, the report controversially recommended allocating a budget consisting of funds from regional oil sales, with over 90 per cent of Iran’s oil and gas resources located in the Ahwaz region. The SCNS also recommended allocating a proportion of the profits from the state petrochemical firms operating in the regime’s Shatt al-Arab ‘free zone’, known as the Arvand Free Zone.

This proposal led naturally to widespread anger amongst Ahwazis who are denied any profit from the sale of their resources by the regime, with the majority living in Third World levels of poverty despite the massive profits from the oil and gas fields.

Ahwazi activists described the report as further irrefutable evidence of the regime’s policy of ethnically cleansing Ahwazis in Iran through mass displacement as a way of eradicating their presence in this region, calling on international human right and legal bodies to adopt an unambiguously critical position and strongly condemn this policy.

Ahwazis have continuously called on humanitarian and human rights organisations to adopt a clear stance in condemnation of the Iranian regime and its officials who are responsible for implementing policies which can only be described as criminal in every sense against Ahwazis, who have been left with nothing more to lose, having been stripped of all rights since the occupation and annexation of their homeland over 95 years ago. Ahwazis have also called repeatedly on the UN Special Rapporteur for Human Rights in Iran, to take action to end the regime’s crimes against Ahwazis in Ahwaz and across the region and to force the regime to desist from these plainly racist policies, and to act in accordance with international laws and treaties.

A: Medical and health demographic change:

Another of the unforgivably cruel policies of the Iranian regime is a deliberate attempt to reduce the fertility rate amongst Ahwazis in the Ahwaz region, thereby reducing the regional percentage of the Ahwazi population in contrast to the immigrant Persians. This is effectively a policy of biological or medical demographic change adopted by the authorities against the Ahwazis. There is no other way for Ahwazis to resist this heinous policy except through international and universal intervention to protect Ahwazis from ethnical cleansing.

Birth through Caesarean section:

According to the global published statistics, we can see that the rate of Caesarean births in the rest of Iran and the world is only 10 to 15%. Meanwhile, Ahwazi activists and doctors in Ahwazi hospitals have reported that the percentage of Caesarean deliveries in Ahwaz is 60%, or 6 out of every 10 births. This means that the percentage in Ahwaz is six times higher than the global norm where only one out of every 10 natural births is delivered via Caesarean. This high rate of Caesarean births has dire consequences for the mothers, their babies and the wider Ahwazi family. This is in the interest of the Iranian regime, as it is harmful in all its aspects. The negative effects include the high expenses, with Ahwazi citizens forced to spend more on medical fees at government hospitals, the negative impact on the baby and the long-term consequences on the mother, with women subject to Caesarean surgery rarely able to bear more than two children. This leads to greatly reduced birth and fertility rates and increasing death rates among Ahwazi women. In addition, the Iranian authorities rely on family planning and population planning programs. These programs are one of the subjects studied at Ahwazi universities which medical students must pass (Heidari, 2019).

Deadly diseases and lethal environment:

After the IRGC launched its sugarcane project on confiscated Ahwazi agricultural lands, hundreds of thousands of hectares of farmland were forcibly seized and sold under the pretext of being essential for the project. Thereafter, the Revolutionary Guard sought to expand the project and began to grab more Ahwazi lands, claiming that they were the property of the nation and belonged to Iran. The farmers were given no right of appeal against these seizures. In return for this involuntary surrender of their land for the sugarcane project, Ahwazis received only deadly incurable diseases from the untreated industrial pollutants dumped into what remains of the region’s rivers by the refineries built on the river banks which use ruinous amounts of water in the refining process before pumping the effluent back into the waterways following the sugar-refining process; these waters are the only source of drinking and household water for millions of Ahwazis, leading to outbreaks of incurable skin diseases such as skin cancer that afflicts Ahwazis more than any group in the world. According to the regime’s own official statistics, “Every year more than 5,000 Ahwazis suffer types of cancer”, accounting for more than half the annual average of just over 8,000 cancer cases documented in Iran despite accounting for less than a tenth of the country’s population (Tabnak, 2015).

Due to this toxic natural environment, many of the Ahwazis who can afford to do so choose to migrate following retirement to the northern Iranian cities with a healthy environment far from the petrochemical companies and sugarcane farms to live far from diseases and epidemics.

According to the head of the Health Centre in Ahwaz, 16 per cent of Ahwazis suffer from pulmonary diseases, asthma and obstruction of the respiratory tract, almost double the percentage in other regions of Iran which does not exceed 9%. The medical official added that the prevalence of these diseases is caused by the sandstorms that regularly completely cover Ahwaz, with dozens of Ahwazis who work in the open air dying every year as a result of exposure to air pollution and suffocation by the choking clouds of fine sand caused by desertification. Even children are affected by these diseases simply from their daily travel to and from school and playing outdoors (ISNA, 2017).

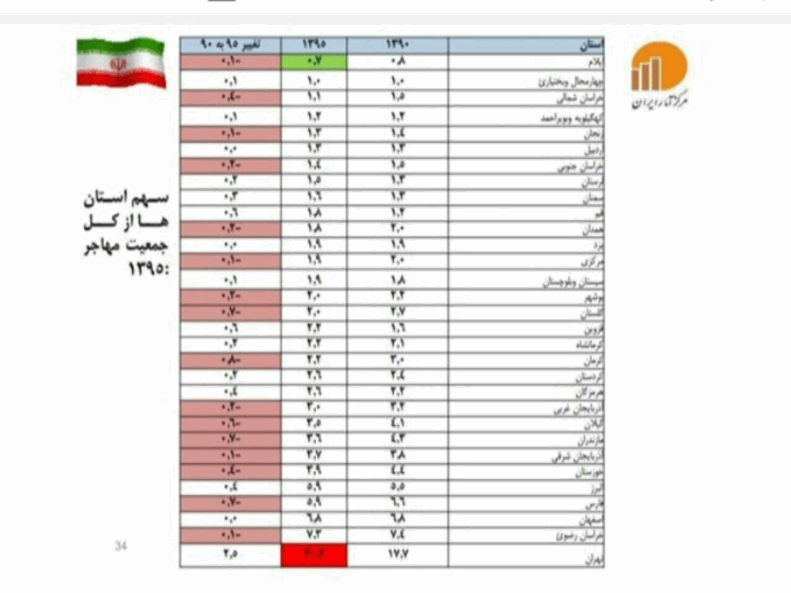

Here, we will review migration statistics from and to Ahwaz in a collection of charts published by the Statistical Centre of Iran in 2016.

Statistical Centre of Iran 2016

Statistical Centre of Iran 2016

Keywords:

Settlement, Immigration, Demography, Ahwaz, Geographical dimension, Population distribution, Environment, Caesarean section.

Summary:

This study dealt with the issue of demography as one of the most important aspects in the Ahwazi-Iranian conflict which has now continued for nearly a century. We have attempted to offer insight into this issue based on official statistics from the Iranian Ministry of Health and Medical Education, the Statistical Centre of Iran and comments by Iranian regime officials.

We wish to emphasise that the Ahwazi people have no means of defence or of confronting this existential threat except through continuing to cling to their identity and land, to teach their future generations to do likewise, and to refuse to engage with Persians or others promoting or implementing the regime’s policies so long as they continue to do so, and to boycott them economically, as they already do to the long-suffering Ahwazi people.

Note: (Some medical sources in Ahwaz hospitals have not been identified in order to protect their safety).

Rahim Hamid is an Ahwazi author, freelance journalist and human rights advocate. You can follow him on his twitter account: https://twitter.com/samireza42

Mostafa Hettehis a writer and journalist:https://twitter.com/mostafahetteh

Editing by Penina Sarah, New York Attorney, Human Rights Advocate and Commentator on the Middle East and National Security Issues.